After Althea

On the 75th anniversary of Althea Gibson's barrier breaking, a look back at her reluctant pioneering, and tracing her legacy to how Black women found their voice at the 2025 U.S. Open.

NEW YORK — Particularly in the United States, the tennis champions who make the greatest and most lasting impacts are not necessarily the ones who won the most.

When the U.S. Tennis Association announced that they were naming the U.S. Open grounds in King’s honor in 2006, it wasn’t because she had won the most—many players had won more—but because of the impact she’d had on society through her advocacy and activism for women, and later for the L.G.B.T. community. Similarly, Arthur Ashe, for whom the Open’s biggest stadium was named when it opened in 1997, hadn’t won the most, either, but his transformational legacy as the first Black man to win major tennis tournaments was what the U.S. Tennis Association wanted to foreground.

In how the story of American tennis is told, the most important characters are the ones that redrew lines outside the court. And at 2025 U.S. Open, on the 75th anniversary of Althea Gibson breaking the color barrier at this tournament, her story is being foregrounded in that tennis storybook like never before. But unlike those other pioneers, the label and role of activist was something Gibson avoided.

“I have never regarded myself as a crusader,” Gibson wrote in her 1960 memoir I Always Wanted to Be Somebody. “...I’m always glad when something I do turns out to be helpful and important to all Negros—or for that matter, to all Americans, or maybe only to all tennis players. But I don’t consciously beat the drums for any special cause, not even the cause of the Negro in the United States.”

For this special edition of Bounces, let’s dive into the history of Black women in tennis taking stands on issues of race, and how it has emerged in a remarkable present at the 2025 U.S. Open.

‘Where is everybody else?’

In a story she has told frequently, Billie Jean King said she had her epiphany at age 12 while playing at the Los Angeles Tennis Club. “I was kind of daydreaming and I noticed everybody wore white shoes, white socks, white clothes, played with white balls—and everybody who played was White,” King told journalist Jessica Luther in 2022. “I remember asking myself, ‘Where is everybody else?’” King says that she knew tennis was a global sport, and thought it could give her the power to change what women, particularly women of color, were experiencing. “‘If I'm good enough, maybe I can make the world a better place,’” King recalled thinking. “Because I really believed already at 11, 12, 13, I knew I was a second-class citizen, but I knew my sisters of color had it worse than I did.”

King wasn’t the only White player thinking of inclusivity in those days. Alice Marble, a four-time champion at the U.S. Open (then called the U.S. Championships in the years before they admitted professionals), wrote a scathing letter in the magazine American Lawn Tennis in 1950 denouncing the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association, the precursor to today’s U.S. Tennis Association, for blocking the participation of 23-year-old Althea Gibson, a talented young Black player. When it came to integration, tennis lagged behind sports like football, boxing, and baseball—where Jackie Robinson had begun playing in the majors three years earlier.

“If tennis is a game for ladies and gentlemen, it’s also time we acted a little more like gentlepeople and less like sanctimonious hypocrites,” Marble wrote. “If there’s anything left in the name of sportsmanship, it’s more than time to display what it means to us. If Althea Gibson represents a challenge to the present crop of women players, it’s only fair that they should meet that challenge on the courts, where tennis is played. I know those girls, and I can’t think of one who would refuse to meet Miss Gibson in competition. She might be beaten for a while—but she has a much better chance on the courts than in the inner sanctum of the committee, where a different kind of game is played.”

Gibson hadn’t been allowed to compete in enough integrated tournaments for Marble to assess her potential, and Marble conceded that she might not prove to be one of the world’s best. “But if she is refused a chance to succeed or fail, then there is an uneradicable mark against a game to which I have devoted most of my life,” Marble wrote, “and I would be bitterly ashamed.”

Gibson was ultimately granted entry into that year’s U.S. Championships. She lost in the second round to Louise Brough, who had won Wimbledon a month earlier, in a nail-biting 6-1, 3-6, 9-7 battle. Her development into one of the best players in the world came eventually: she won her first major at the French Open in 1956, and back-to-back titles at both Wimbledon and the U.S. Championships in 1957 and 1958.

Because of strict rules enforcing amateurism in those days, Gibson could no longer compete at the biggest tournaments once she decided to turn professional. “Being the Queen of Tennis is all well and good, but you can't eat a crown,” Gibson later wrote. Gibson’s early retirement from the sport cleared space for other players, notably Margaret Court, to sweep up titles in her absence as the 1960s began.

‘Althea Gibson, Private Individual’

Gibson demurred on opportunities to use her status as a tennis champion to champion causes beyond the court. “I try to steer clear of political involvements and make my way as Althea Gibson, private individual,” she wrote.

Though Gibson wanted distance from controversial topics, others sought to harness her symbolic power—including her own government. The U.S. State Department was eager to use Gibson as a symbol, sending her on a goodwill tour of Southeast Asia along with three White players to combat negative international perceptions of race relations in America. “The State Department people had warned me that I probably would be asked a lot of questions about the Negro’s life in the United States,” Gibson wrote. “They said it was up to me to say what I thought was right, and all they asked was that I remember that I was representing my country.”

When Gibson won Wimbledon for the first time in 1957, London’s Evening Standard said it was a credit to American race relations. “It shows that somewhere in the great American dream there is a place for black as well as white, in this instance for a courageous and conscientious Harlem urchin.”

Such statements did not resonate with Gibson, who downplayed her own significance as an agent for change. “I am not a racially conscious person,” Gibson wrote.

“I don’t want to be. I see myself as just an individual. I can’t help or change my color in any way, so why should I make a big deal out of it? I don't like to exploit it or make it the big thing. I'm a tennis player, not a Negro tennis player. I have never set myself up as a champion of the Negro race.

“Someone once wrote that the difference between me and Jackie Robinson is that he thrived on his role as a Negro battling for equality whereas I shy away from it. That man read me correctly. I shy away from it because it would be dishonest of me to pretend to a feeling I don’t possess. There doesn't seem to be much question that Jackie always saw his baseball success as a step forward for the Negro people, and he aggressively fought to make his ability pay off in social advances as well as fat paychecks. I'm not insensitive to the great value to our people of what Jackie did. If he hadn't paved the way, I probably never would have got my chance.

“But I have to do it my way. I try not to flaunt my success as a Negro success. It’s all right for others to make a fuss over my role as a trail blazer, and, of course, I realize its importance to others as well as to myself, but I can't do it.”

Gibson’s decision to decline the mantle of a civil rights leader was seen by some Black critics as a dereliction of duty. “I am uncomfortably close to being Public Enemy No. 1 to some sections of the Negro press,” she wrote. “I have, they have said, an unbecoming attitude; they say I'm bigheaded, uppity, ungrateful, and a few other uncomplimentary things. I don't think any white writer ever has said anything like that about me, but quite a few Negro writers have, and I think the down-deep reason for it is that they resent my refusal to turn my tennis achievements into a rousing crusade for racial equality, brass band, seventy-six trombones, and all. I won't do it. I feel strongly that I can do more good my way than I could by militant crusading. I want my success to speak for itself as an advertisement for my race.”

‘A World That Didn’t Want Us’

Gibson’s aversion to agitation was typical of Black tennis players in the mid-20th Century. This was, largely, often a matter of self-preservation, knowing how precarious their welcome into the overwhelmingly White sport had been.

Gibson was the first Black tennis player to win major titles, but she was hardly the first Black person to play the sport. There are records of tennis being played at HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) as early as the 1890s, when the modern sport was less than two decades old. When the U.S. Lawn Tennis Association didn’t allow Black players in its tournaments, Black tennis enthusiasts created their own organization, the American Tennis Association (A.T.A.), which was open to all races.

The first A.T.A. National Championships were held in 1917 in Baltimore, attracting the best Black players from around the country. The best of them was Ora Washington, who won eight national championships in singles between 1929 and 1937. Though effectively the tennis equivalent to baseball’s storied Negro Leagues, the A.T.A. has continued as an organization long after the color barriers were officially broken, building community and developing talent.

Preparing Black players to compete as integration began came with additional challenges. Coaches like Dr. Robert Walter Johnson—who led the A.T.A.’s national development program from his home in Lynchburg, Virginia where he coached Gibson, Arthur Ashe, and many more—put as much emphasis on sportsmanship, manners, and comportment as he did on tennis.

“Any time these players went outside of their community to compete, all eyes were on them,” said Katrina Adams, a Black player who later became president of the U.S. Tennis Association. “They had to be the best behaved, so that there was no reason for anyone to accuse them of anything more than playing great tennis.”

Johnson’s grandson Lange said that Black players who were playing the newly integrated tournaments made major concessions in the name of deference, including conceding close calls to avoid conflict. “If the ball was two inches out, they would call it in because they didn’t want to create any tension,” Lange Johnson told me. “Everything was about being a model citizen, a model student, and making sure you didn’t draw any attention to yourself.”

Leslie Allen was one of the players Johnson had coached in Lynchburg. “Essentially, as I look back on Dr. Johnson, he was preparing us for a world that didn’t want us,” Allen told me. Integration hardly meant that all hurdles facing Black players were removed, including down to the junior tournaments, where she said the best Black players were often pitted to face one another in early rounds.

“It happened too often to be coincidental,” she told me. “There was that expectation that that was what was going to happen, which was just another way for institutional racism within the sport to happen. So that was the landscape that any player that was trying to excel in tennis knew were up against.”

Allen was the first Black woman to win a singles title on the professional tour, winning the Avon Championship of Detroit in 1981. She said that in her era, Black women on tour were more focused on the challenges of building women’s tennis as a professional sport, rather than race-specific topics.

“Partly generationally, so much of the fight in tennis for women was: Can we get equal prize money? Can we play on the main stage? Can we play a feature match at night? Those were the issues,” Allen said. “Not to say race wasn't an issue, but those were the fights that we were trying to make so that tennis was a viable career, so a female athlete could be taken seriously.” Part of being taken seriously, Allen said, was being amicable. “In trying to build a brand for women's tennis, if they felt like we were all, for lack of a better term, rabble-rousers, it was going to be that much harder to attract sponsors,” she said.

Though microaggressions and other slights happened constantly at tournaments, Allen said, choosing to make a stand came with costs. “You sort of had to make a decision as a person of color: am I going to speak out and risk what I have? You had to decide which battles you were going to fight. So, you know, mostly the battle that I feel like I was fighting during my tenure playing was just trying to develop women's tennis. And quite frankly, nobody was talking a lot about race and racism in the 80s.”

Though Gibson had broken through, and Arthur Ashe also won major titles on the men’s side, Black tennis players were still treated as oddities and anomalies during Allen’s career. “It was not in the consciousness of people that people of color played tennis,” Allen told me. “It wasn't in the greater African-American consciousness, necessarily, and definitely not in the White consciousness that that was a thing. People today still say: What, did you run track? What, did you play basketball? It takes a few times before they get to tennis.”

‘You trynna do that Williams sister thing?’

The biggest transformation to the awareness of Black people in tennis, of course, was the arrival of the Williams sisters.

Frances Tiafoe, who in 2022 became the first Black American U.S. Open men’s singles semifinalist at the U.S. Open in 50 years, said the Williamses were synonymous with tennis in his community. “If you're in the Black community and you talk about tennis, they'll be like, ‘Oh, you trynna do that Williams sister thing?’” Tiafoe said. “They're so big. They're huge. I mean, otherwise, predominantly Black sports are football, basketball. But, you know, people come out and watch tennis to see them.”

Tiafoe said that the Williamses had forged a connection with Black viewers not just with their success, but with their authenticity. “It's the passion component, right?” he said. “Because I mean, you see how much passion, dedication they have. You know, loud ‘C’mon’s, how fierce they are, being competitive. It's like, wow, tennis is actually cool to play.”

Tiafoe said he was most struck when at the 2015 U.S. Open during Venus and Serena’s quarterfinal against one another, seeing all the celebrities who came to watch them. “These guys are humongous—I mean, Oprah ain't coming to watch my ass,” he said in 2022, laughing. “At least not yet, anyway. But seriously, man, that's what they bring. I'm happy to call them friends, colleagues, whatever.”

The Williamses brought meaning to not only future generations, but to their predecessors, Leslie Allen, who had been the first Black champion on the women’s professional tennis tour in 1981, said people seemed to better understand her own accomplishments from decades earlier once the Williamses arrived. “I knew when I saw a homeless guy ask me if I was ‘that Vanessa Williams’ because I had a Wimbledon bag with me on the subway,” Allen said, laughing. “I was like, okay, it's universal! Now, everybody knows Black women play tennis.”

‘The Cost of It’

Allen said that she had always been politically aware, and had always known that sports and politics were intertwined, from Cassius Clay to Olympians Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who had made Black Power salutes with their raised fists on the podium at the 1968 Olympics. “That iconic picture, I loved,” Allen said. “I thought it was great and inspirational as a kid, but I also knew the cost of it.”

Allen said her own decision to speak out came well after her retirement, after the Black Lives Matter movement had begun. “At some point, I decided it’s not my job to make White people feel comfortable about racism—it's just not…it was gradual, and for sure after George Floyd, it was like you ripped the Band-Aid off.”

Though the Williamses had immense symbolic power as Black women dominating a historically White sport, they rarely took overtly political stands, often citing their faith as Jehovah’s Witnesses, a religion which prohibits adherents from getting involved in politics and even voting. The most notable exception came in 2000, when Serena withdrew from a tournament in Charleston to adhere to the NAACP’s boycott of South Carolina over the Confederate flag flying at the state capitol. “My decision to not play in South Carolina was based on a much deeper issue and one that I feel strongly about," Serena, then 18, said.

For the rest of her career, Serena overtly avoided political entanglements, like when she was asked at a press conference at Wimbledon in 2022 for her reaction to the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. “I think that's a very interesting question,” Serena said. “I don't have any thoughts that I'm ready to share right now on that decision.”

So though Naomi Osaka had modeled so much of her life after Serena, what she did in the summer of 2020 by foregrounding the Black Lives Matter movement and wearing names of victims of police violence on the masks she wore onto court at the U.S. Open was something uniquely her own, albeit building on generations before her. “I wish Arthur Ashe had been alive to have seen that happen,” Pam Shriver said of Naomi. “And Althea Gibson, just because back in the day, you would never have picked a tennis player to be the athlete that would do something that bold.”

When Allen heard Naomi speaking out, she said she took pride that she and other Black women of previous generations had laid a solid foundation that made what Naomi was doing less precarious. “She wasn't going to be permanently ostracized, right?” Allen said. “She was not going to end the opportunities for women of color to play tennis, because we're entrenched into the mainstream of tennis now. So each little step that every generation took, has allowed and afforded her that opportunity…She wasn't going to be Kaepernicked, because she was so important to the sport. I was proud of her because I felt as though this is what we've all done over the years. We were really silent so she could go on to do this.”

The Sparkling Star of a Diamond Anniversary

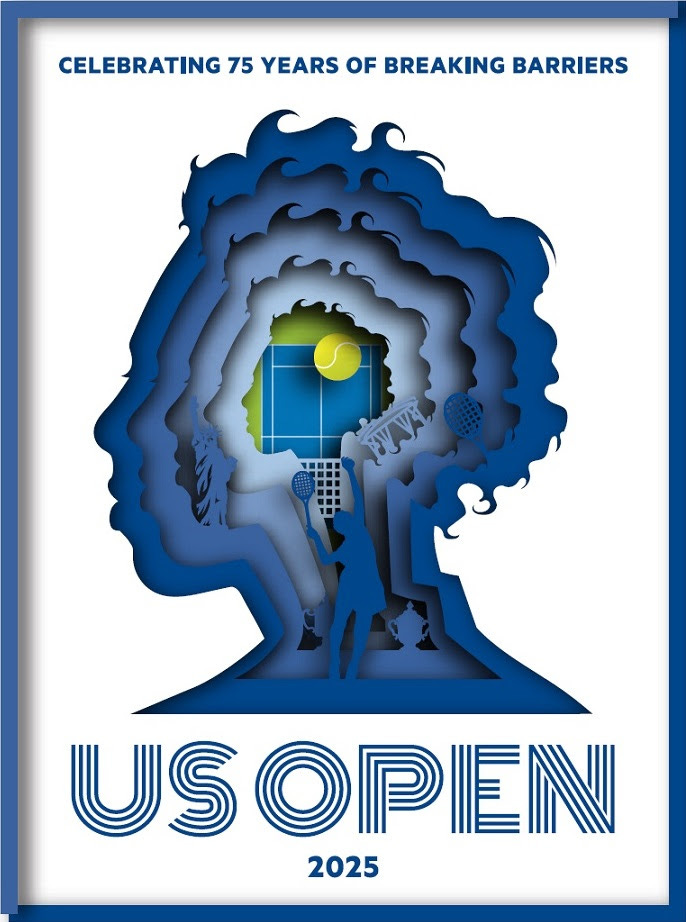

To celebrate the 75th anniversary of Gibson’s debut in the 1950 U.S. Championships, the U.S. Open commissioned Melissa Koby—the first Black theme artist in US Open history—to make artwork for this year’s event which foregrounded Gibson and her history.

Koby’s artwork could be seen as a fitting cover for the story contained within the book of this year’s tournament. The marquee U.S. Open fourth round match is a match between two Black stars, Naomi Osaka and Coco Gauff. The breakout star of the tournament has been Taylor Townsend, who won over multitudes of new fans and admirers both for how she has played and won, and how she handled a moment which many saw as racially charged.

Here’s how big Townsend has become at this 2025 U.S. Open: she held a lengthy 15-minute press conference in Room 1 on Saturday after a doubles match. In the last question of that engagement, I asked Townsend how Gibson’s diamond anniversary might have reflected on everything she’s done this week.

Here’s how Townsend responded:

If you enjoyed this article, I think you will enjoy Bounces, and I encourage you to subscribe to help keep this sort of about tennis and the culture around it going!

Beyond the paywall below for Bounces subscribers, a look ahead at matches to watch as fourth round play begins Sunday at the U.S. Open. Thanks for reading Bounces! -Ben