Legends Only

In the Australian Open final between Carlos Alcaraz and Novak Djokovic, it became clear that mortals no longer need apply in men's tennis.

MELBOURNE, Australia — There were three Australian Open champions standing on the “AO”-shaped rostrum inside Rod Laver Arena on Sunday night as the trophies were being handed out, personifying both what tennis has become and what it once could be.

There was Novak Djokovic, a 10-time champion in Melbourne and 24-time major champion—both all-time men’s tennis records—who was holding the runner-up plate for the very first time. Had the 38-year-old won on Sunday night, he would’ve become the oldest major men’s singles winner ever.

Djokovic was followed onto the stage by Carlos Alcaraz, who had just beaten him in four sets—2-6, 6-2, 6-3, 7-5—to win his first Australian Open title, thereby becoming the youngest-ever male player to complete a Career Slam at just 22 years old.

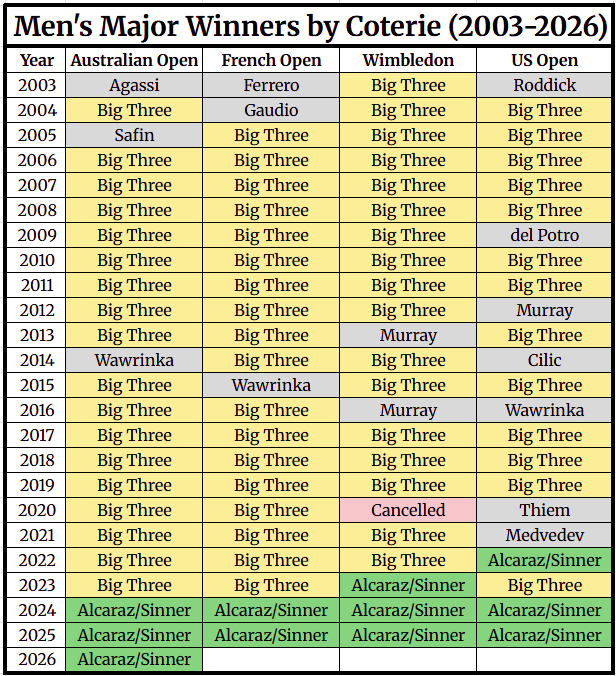

In this era of men’s tennis, having a historic superlative to your name feels like table stakes for winning a major. After all, it’s now 17 majors in a row that have been won by either the Big Three or the new Alcaraz-Sinner duopoly; that’s the second-longest streak by the two coteries since the Big Three reeled off 18 in a row from the 2005 French Open (Rafael Nadal’s first major title) through 2009 Wimbledon (Federer’s 15th major, which broke Pete Sampras’s previous record of 14; Sampras now sits in a distant fourth).

And then there was the third champion on the “AO”-shaped stage on Sunday: Mark Edmondson, whom tournament organizers picked to hand out the trophy to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his 1976 Australian Open title.

You’ll be forgiven if you don’t know anything about Edmondson, who is likely one of the most obscure living major champions. If you know his name, it’s likely for the trivia fact that his win from a half-century ago remains the last victory here by an Australian man.

He was almost completely unknown before his win: ranked 212th when he won his Australian Open title, Edmondson had only gained entry into the 64-player draw after many of the world’s top players didn’t make the trip. As detailed by Len Ferman recently, Edmondson had been working odd jobs as a handyman and janitor to fund his fledgling tennis career in the weeks before his run in Melbourne.

Edmondson never replicated that stunning run, but nor was he a total flash-in-the-pan at the majors: he reached another Australian Open semifinal five years later, and a Wimbledon semifinal a year after that. He also won five men’s doubles majors, rounding out a very tidy career. But it’s safe to say that Edmondson, whose career-high ranking topped out at 15th, has never been mentioned in any “Greatest Of All Time” discussion.

Still, it was nice to see Edmondson appear in the context of this clash between two guys with history on the line, if only to remind us that, once upon a time, guys like Edmondson could become major champions. There could be surprises in eras past; a men’s draw could end on the weekend with an “any given Sunday”-style winner.

But while Edmondson was an everyman, what Djokovic and Alcaraz have achieved in their careers feels fully unattainable, even to nearly all the other professional players in their locker room.

Alcaraz, especially, defies any sense of possible emulation.

“What you’ve been doing, I think the best word to describe it is: historic,” Djokovic told Alcaraz in the trophy ceremony. “Legendary.”

In his press conference—which I will have more about on Bounces very soon—Djokovic expounded on that assessment of the legend of Carlos Alcaraz.

“Already a legendary tennis player that made, already, a huge mark in the history books of tennis, with only 22 years of age,” Djokovic said. “It’s super impressive, no doubt about it.”

In the Spanish portion of his press conference, Alcaraz was asked about what he felt about that declaration by the winningest player in his sport’s history:

“To what extent does it impress you that someone like Novak would describe you as a legend? Do you consider yourself, or see yourself, at such a young age, as a 22-year-old legend?”

Alcaraz demurred, at first, but didn’t deny that he’s clearly onto something with his career.

“I don’t think a legend is forged in three or four years on the tour,” Alcaraz said in Spanish. “Obviously, I think that for what I’ve achieved, many people might call me a legend: seven Grand Slams, several Masters, 25 titles, almost 60 weeks as world No. 1. There are many people who might think they could already consider me a legend if I retired today, right now.

“But I believe a legend is forged over a long period of time. Seeing a player year after year, going to the same tournaments, with the same ambition, the same hunger, the same passion, and creating a feeling in the people who watch—that’s where a legend is really forged.

“So I’d like people not to call me that now, but someday—five years from now, ten years from now, whenever—then they can say that my career was legendary, that I’m a legend of tennis. That’s what would make me proud.”

On a map, a legend is most often found in the lower-right corner. That’s where Australia is most often found on a map, too.

Bounces readers will know that I’ve pushed back on setting expectations too high for Alcaraz, particularly in his 2025 Netflix docuseries.

But Alcaraz was ready to talk lots of big talk, it was clear, on Sunday, so I thought I’d ask him about the few remaining boxes he hasn’t yet checked.

Ben Rothenberg, Bounces: Wondering for you, now that you have this big goal accomplished in the career slam, how you think about future goals, if there’s anything else you want to do? Say, winning every Masters event? There’s still three [Canada, Shanghai, Paris Indoors] you haven’t won. ATP Finals?

And as you think of goals, where does the fire and the drive to keep wanting more come from, when you have already done so much at such a young age?

Carlos Alcaraz: Well, I hate [to] lose (smiling), so that’s my motivation. Trying to lose as [little] as I can.

Yeah, there are some tournaments that I just really want to win at least once, a few Masters 1000s. I just really want to complete all the Masters 1000—trying to win at least once, every Masters.

And, obviously, the ATP Finals and the Davis Cup. The Davis Cup, it is a goal as well. I really wanted to achieve that for my country, for Spain.

So I’ll set up some other goals for the season, and I will try to be ready to try to get those goals.

For more on Carlos Alcaraz—his greatness, where he goes from here, his coaching situation, and more—check out the episode of No Challenges Remaining which Tumaini Carayol and I recorded hours after the men’s final.

We also discussed and defended, in the last third of the show, the spate of U.S. politics questions which American players got in press conferences during the first week of this Australian Open.

For more on this Australian Open men’s final—particularly Novak Djokovic’s perspective, in English and Serbian—stay tuned to Bounces; that’s coming very soon for paid subscribers.

Thanks for reading Bounces! -Ben

I'd like to be nice, but I'm going to rain a little on Mark Edmondson's party. By my count the field had three players then ranked in the top 20. To Edmondson's credit, he beat two of them, Ken Rosewall (who was 41 at the time) and John Newcombe. People tend to get excited about Edmondson's accomplishment because they see that he was ranked 212. But his ranking is relevant to his accomplishment only if a lot of the top-ranked guys played. The 16th seed, Syd Ball, had an ATP ranking of 116 when the tournament started. The 1976 AO (which started in December 1975) had the field of an ATP 250 today.

Free link to article by Simon Briggs, with some wild and woolly weather in Battle of the Moustaches.

Mark Edmondson interview: I spent a week cleaning windows, then won the Australian Open

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/gift/2ade0cc5fe62ed5c