Lights, Cameras, Inaction

As electronic eyes keep prying and spying at the Australian Open, tennis authorities remain unresponsive to player privacy concerns.

MELBOURNE, Australia — Of course she was on camera; everything here is.

As Coco Gauff suffered one of the most stunningly lopsided losses of her career—a 6-1, 6-2 defeat in the Australian Open quarterfinals on Tuesday—the 21-year-old American remained composed on court. By keeping her cool she was keeping a vow she had made to herself after breaking a racquet during a loss in the 2021 French Open quarterfinals.

“I said I would never do it again on court, because I don’t feel like that’s a good representation,” Gauff said Tuesday night.

Gauff later added: “I don’t try to do it on court in front of kids and things like that. But I do know I need to let out that emotion, otherwise I’m just going to be snappy with the people around me—and I don’t want to do that, because they don’t deserve it. They did their best; I did mine. Just need to let the frustration out.”

So after Gauff had shaken hands with the victorious Elina Svitolina and walked off of the stage of Rod Laver Arena—and further stepped into a walled-off side ramp near a service corridor—Gauff let her frustration flow freely, and whaled away on her racquet.

But for the millions watching at home and on social media, Gauff was still fully in public view, caught by one of the Australian Open’s many interior cameras. In fact, on ESPN Deportes, the play-by-play commentator commentated on Gauff’s swings as if she were still playing the match.

“Pobreciiiiita,” he said after Gauff’s seventh and final swing.

In her post-match press conference, Gauff lamented how her venting was beamed to the world.

“I tried to go somewhere where there was no cameras,” she said. “… I tried to go somewhere where they wouldn’t broadcast it. But, obviously, they did. So, yeah, maybe some conversations can be had, because I feel like at this tournament the only private place we have is the locker room.”

Same Story, Different Year

Those conversations have already been happening at this tournament for seven years, but nothing has changed.

The Australian Open began by introducing a few behind-the-scenes cameras a decade ago, and added an array of high-tech, high-mounted cameras around various tournament corridors for the 2019 Australian Open. That year, I wrote a feature for The New York Times about how the “Australian Open, the most remote Grand Slam event, is offering voyeurism without the voyage in a way no other tournament does.”

When I asked many of the sport’s biggest stars that year about being silently surveilled, few of them realized just how much of their time in the inner sanctum of the tournament was suddenly being broadcast to the wider world.

Here’s more from that article:

Players and their entourages are often unaware how many of their movements are monitored and magnified by cameras that follow them as long and as closely as possible.

The tournament installed a few fixed cameras three years ago and now curates a feed from many remotely operated cameras that monitor the recently renovated players’ areas at Melbourne Park. The footage appears in segments of television broadcasts and can also be seen online in a stand-alone stream.

“We live in Big Brother society,” top-ranked Novak Djokovic said of the cameras. “I guess you just have to accept it.”

And so the tournament that branded itself the Happy Slam has become the Orwellian Open…

…Craig Tiley, the tournament director, would not say how many cameras were used, but he called them “a rich source of content” that would complement match coverage and reveal a more complete picture of the sport and its culture.

Tiley said that the mounted cameras were intended to create a single source of video for rights-holding broadcasters, rather than having the hallways clogged with various camera operators and their equipment.

Tiley said that there were “strict protocols about what could be shown, but that players were not all explicitly warned about the cameras or told to sign waivers agreeing to be shown at any time. The high-definition cameras are in areas otherwise off-limits to the public and, this year for the first time, to accredited news media.

“The cameras are round and black and hang down from the ceiling,” Tiley said. “They are very easy to see, and we have had dozens and dozens of players and coaches playing up to them.”

Most of the moments caught on camera are deeply mundane, but any moment could go viral. Back in 2019, one camera caught defending champion Roger Federer trying to enter the locker room without his accreditation and being stopped by a security guard.

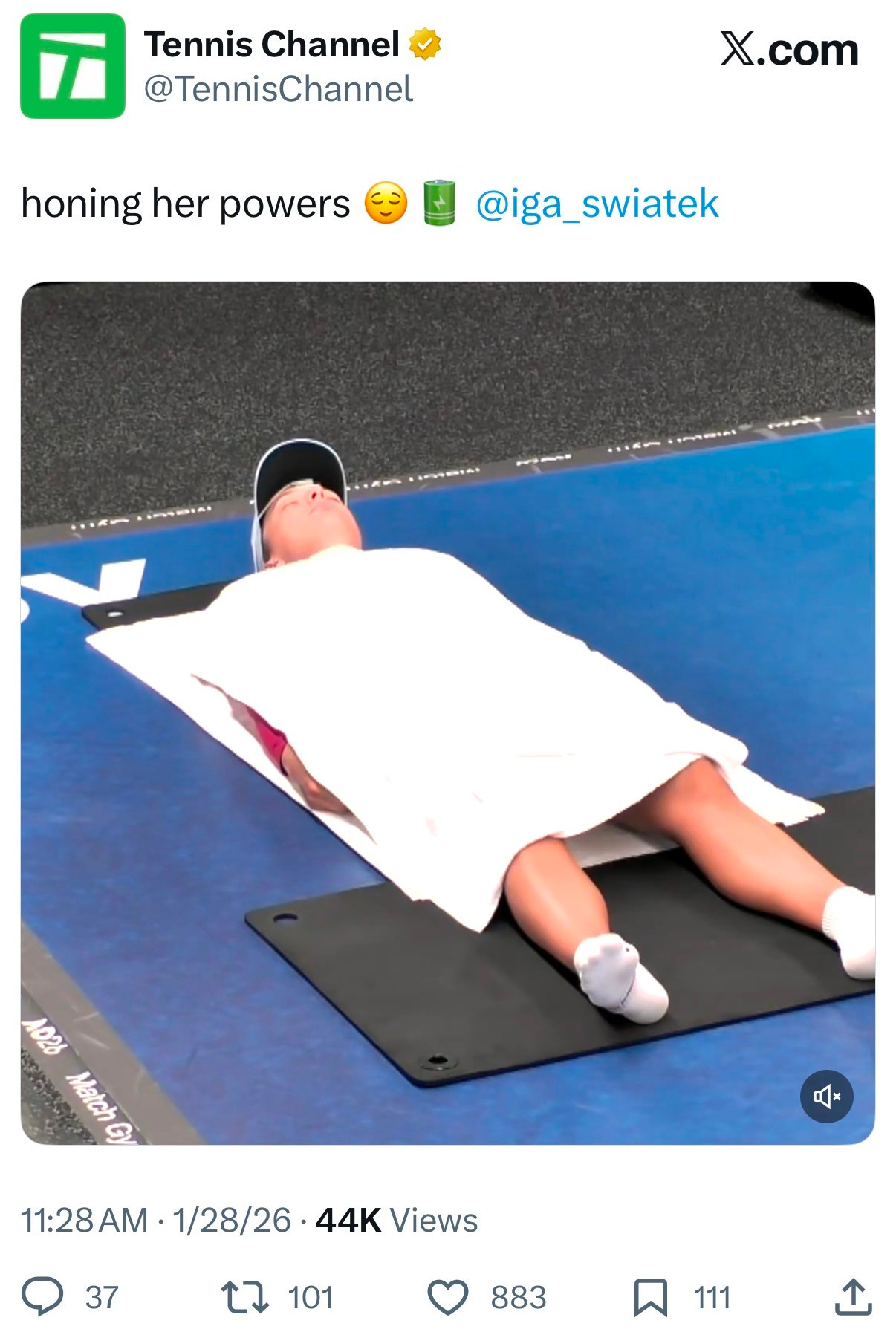

Seven years later, a similar scene went mildly viral again when second-ranked Iga Swiatek was also stopped by security when she did not have her credential with her.

The scenarios have not changed much backstage, but the frustration of seven years of overexposure has accumulated and fermented, as Swiatek’s withering response indicated when I asked her about the topic after her quarterfinal loss on Wednesday.

Ben Rothenberg, Bounces: Iga, I wanted to ask about something that Coco was actually talking about last night, about the cameras backstage at the tournament, filming people. I know you got filmed recently for getting your credential and stuff, and they just sort of are always on camera in a lot of different tournament areas. I’m wondering if you think there should be more privacy for players and their teams as they’re back there? How do you see the balance of that versus them trying to have entertainment and constant content coming out?

Iga Swiatek: Yeah, the question is: are we tennis players, or are we, like, animals in the zoo where they are observed even when they poop, you know?

OK, that was exaggerating obviously, but it would be nice to have some privacy. It would be nice also to, I don’t know, have your own process and not always be, like, observed.

Like, for example, I don’t know, in other sports you have some maybe technical things that you want to do, and you have—I don’t know, honestly. I don’t follow other sports that much, but I guess it would be nice to have some space where you can do that without the whole world watching.

Swiatek, who is a reliably intense and idiosyncratic presence backstage at tournaments as she does her pre-match rituals, reliably gets images of herself clipped by tournaments and broadcasters, turning her into the butt of jokes.

Swiatek said she appreciated how two of the majors, Roland Garros and Wimbledon, have semi-off-site facilities where players can practice with a bit more privacy.

“There are some spaces that you can at least go when you need to,” Swiatek said, referring to Roland Garros’ Jean Bouin and Wimbledon’s Aorangi. “But there are some tournaments where it’s impossible, and you are constantly observed; if not by the fans who can just buy some ground passes and go to your practice, then by the cameras.”

Swiatek made her displeasure with the overreach clear.

“For sure it’s not simple. I don’t think it should be like that, because we’re tennis players,” Swiatek said. “We’re meant to be watched on the court, you know, and in the press [conferences]. That’s our job. It’s not our job, like, to be a meme when you forget your accreditation. It’s funny, yeah, for sure; people have something to talk about. But for us, I don’t think it’s necessary.”

Swiatek was far more succinct when I followed up and asked if she had “ever talked to the tournament about it here?”

Her reply: “What’s the point?”

That sense of pointlessness pervaded. Though none of the players I asked on Wednesday seemed to enjoy the cameras, a sense of powerless resignation and helpless futility seemed to win out.

Jessica Pegula, a longtime member of the WTA Player Council, had seen Gauff’s viral reaction, and also knew that the topic had long been brewing in player leadership meetings. Swiatek’s response to me might have been harsher because she had just lost, but the victorious Pegula was equally and thoroughly animated by the topic as well.

Here’s our exchange:

Ben Rothenberg, Bounces: Coco and Iga talked about the cameras backstage at this tournament, and not feeling like they had privacy; I don’t think Coco realized she was in a camera area when she broke a racquet after losing last night.

I’m wondering, for you as a player council person who has dealt with these kind of things, what do you think about the issue of player privacy and protection, safe spaces for them, versus this want the tournament has for constant content to make a reality show?

Jessica Pegula: Yeah, I’m not a fan of the cameras. I saw that last night, and I was, like, ‘Geez.’ It’s the same thing when Aryna lost the [2023 U.S. Open or 2025 Australian Open] final, I was, like, ‘Can you just let the girls have like a moment to themselves?’

Honestly we were talking about cameras years ago. I remember when Madi Keys, her number one priority on council was: ‘We have to stop with these cameras—this is crazy.’

I think they ended up putting up signs so people knew there were cameras. But this year it feels even worse. Like, I’ll be in the gym, and [on a television screen there] there’s video of me, like, walking into the site. I saw people that didn’t even know was happening in areas that you don’t think someone is kind of watching you. It’s in every single hallway.

Coco wasn’t wrong when she said the only place is the locker room—which is crazy. You know, you’re just kind of going about your day. To feel like someone is constantly filming you, I saw online people were zooming in on players’ phones and stuff like that. That’s so unnecessary. I just think it’s really an invasion of privacy.

I mean, we’re on the court on TV; you come inside, you’re on TV. Literally, the only time you’re not being recorded is when you are going to shower and go to the bathroom. I think that’s something that we need to cut back on, for sure.

Yeah, I don’t think what Coco did was wrong; I don’t think what Aryna did was wrong. It’s just people happen to be watching it. You just feel like you’re under a microscope constantly.

Then people obviously post it online, and then they either take it out of context or judge you on a moment that shouldn’t be a moment. It should be a private moment. I really, really am not a fan…

…Yeah, I think Coco was right to call it out. It’s definitely not something new, especially on a council perspective. It seems to be worse here than maybe other years, so I think now it’s going to definitely be talked about and highlighted again moving forward.

Ben Rothenberg, Bounces: Do you think this tournament has it more than other tournaments?

Jessica Pegula: It seems like it, yeah. I remember a few years ago it was a conversation, and then I think they put up signs to kind of notify people, but like, no one is looking at a sign. That doesn’t make it better.

But, yeah, it’s a little—very intrusive.

Ben Rothenberg, Bounces: In terms of what you were saying before about the cameras, how do you get Tennis Australia or whoever it is to be responsive if this has been an issue? They first started doing the hallway cameras in 2019, so it’s not a new thing. How do you get them to listen?

Jessica Pegula: I’m not really sure. I guess this kind of goes back to a lot of the Grand Slam [negotiation] stuff. Having a line of communication with them would be fantastic; we don’t really have that right now.

So, again, this would be maybe an issue where we would be like, ‘Hey, nobody wants these cameras, it’s really invasive, it’s intrusive.’

I’m all for growing a Slam and you want content for fans, but at some point it’s a little too much. I mean, I think that’s where maybe that comes into play.

Like I said, as Coco kind of mentioned it and touched on it yesterday, I think that will definitely get more eyes on it. Hopefully, they can pull back some of that stuff, but we won’t know until next year—or maybe if they decide to respond and have a more open communication with us.

Another veteran of tennis politics whom I wanted to ask about the topic was Novak Djokovic. Since Djokovic had called the cameras a sign of “Big Brother society” in my original 2019 story, I was curious how he would feel about the issue seven years later.

Djokovic began with empathy for Gauff, and then sounded similar laments to Swiatek’s and Pegula’s, with even more of a sentiment of surrender.

“It’s really sad that you can’t basically move away anywhere and hide and fume out your frustration, your anger in a way that won’t be captured by a camera,” Djokovic said. “But we live in a society and in times where content is everything, so it’s a deeper discussion. I guess it’s really hard for me to see the trend changing in the opposite direction, meaning we [would] take out cameras.

“It’s only going to be as it is or even more cameras,” Djokovic added. “I mean, I’m surprised that we have no cameras while we are taking shower. I mean, that’s probably the next step.

“I’m against it. I think there should be always a limit and kind of a borderline where, OK, this is our space. But commercially, there’s always a demand [to] know how players warm up, what did they say when they speak to their coaches, and what’s their cooldown. They want to see us arriving in the car and walking through corridors. So, yeah, you’ve got to be careful, in a sense.

“I [have been] on the tour for quite a bit, so I remember the time when we didn’t have so many cameras; then that transition of really getting used to having an eye—that you don’t hear and may sometimes forget about—always on you is frightening. Because at times you want to relax and maybe, I don’t know, be yourself in a sense that you don’t want [the] public to see.

“But it’s really hard for me to see that that’s going backwards, you know? It’s just something that I guess we have to accept.”

Tennis Australia’s Response

When I reached out to Tennis Australia for comment on player criticism of their surveillance systems, they responded with this statement to Bounces:

Striking the right balance between showcasing the personalities and skills of the players, while ensuring their comfort and privacy is a priority for the AO.

Each year we provide more private spaces for players where they can relax, focus on their preparation and work with their teams privately. This includes a player quiet room and strategy rooms, a sleep room, private locker rooms, medical, health, wellbeing and beauty rooms.

Cameras capturing behind-the-scenes are positioned in operational areas where the players warm up, cool down and make their journey to and from the court. This is all designed to provide fans with a deeper connection to the athletes and help them build their fan base.

Our goal is always to create an environment that supports the players to perform at their best, while also helping fans appreciate their skill, professionalism and personalities.

As always, we value feedback from the players and will continue to work collaboratively to ensure the right balance.

Doing the Rights Thing

I elided over one section of Pegula’s earlier answer because I wanted to address it separately. When it comes to battles over backstage images—like the emerging dispute between the Australian Open and top players over WHOOP wearable monitors—there’s an element of proprietary positioning and control.

“I’ve had the tournament tell me to take down some stuff because they own footage and stuff like that,” Pegula said with exasperation. “I’m, like, ‘Are you serious?!’ I post something that has to be taken down, but then you can see me on every single hallway that I’m walking in and post it online? It’s not cool.”

Just as the tournament wants content out the players, so too do the players want content out of the tournament. More and more players now have their own YouTube channels which they want to fill with self-serving content; players requested credentials for such personal content creators in record numbers at this Australian Open. Those player-paid producers aren’t livestreaming their unedited images to the world the way the tournament’s cameras are, but there are still concerns that they could be places which could interfere with player privacy or rightsholders.

One small dust-up came after I was nearly done with this story. After Ben Shelton’s tournament ended in a quarterfinal loss to Jannik Sinner on Wednesday night, Shelton’s videographer, Josh Tu, was filming Shelton’s news conference from the press seats, presumably for the next feature on Shelton’s recently-created YouTube channel.

As Shelton and his team were exiting the interview room once he’d finished, tournament staff approached Tu and asked him why he had been filming and who he was with; Tu replied that he was with Shelton himself and pointed toward one of the tournament’s star attractions. Was that answer satisfactory? It wasn’t clear, but Tu quickly walked away from the confrontation to continue shadowing Shelton.

That interaction didn’t surprise me whatsoever, given my own experiences with Tennis Australia’s constant monitoring of on-site journalists. Ever since I first came here, there have been strict prohibitions on photography in any of the media areas of the tournament. This would be understandable if these were invasions of player or staff privacy, but taking images without people is also banned; in fact, last year I was warned after tweeting a photo of the empty press conference podium, which I only did to show how Daniil Medvedev was no-showing his press conference after his loss to Learner Tien. This year, at least, photos in the interview rooms are newly permitted.

Ironically, I would have liked to have included a photograph in this story of what these behind-the-scenes cameras look like, in order to better illustrate what the players see; in fact, there are at least three of the cameras which I regularly walk past when I walk from my desk to the interview terrace.

But even though these cameras capture and transmit images of myself and other reporters all day long, we are not to capture images of them. As I was working on this story, I was warned anew by a Tennis Australia official that I was not allowed to take pictures of anything in a “behind the scenes area” of the media center, even if it was just a picture of an inanimate object that was, itself, taking pictures of me.

So I don’t have pictures of these Australian Open cameras, but I found images of a very similar model on the Panasonic website in case you want to see the all-seeing.

It didn’t feel coincidental that in 2019, the same year which Tennis Australia first added cameras to many of its corridors, they also barred journalists from accessing those same pathways. Those were areas which we had always previously been allowed to freely enter in order to find and meet subjects for interviews, but Tennis Australia now keeps the area limited to its own cameras.

But still, there are many tennis stories to be told, both of what is seen and unseen, and I’ll try my best to keep bringing them to you here at Bounces.

To support the independent journalism I do in tennis, thanks for reading, sharing, and supporting Bounces! -Ben

Channel 9 tennis coverage in Australia just did a ‘behind the scenes’ segment showing the player area, gym, spa, laundry, tournament control centre, etc. It also included close up footage of the cameras…The timing of this seems uncanny

Craig Tiley has always seemed like an ass. If he comes to the USTA and puts his ass-y imprint on the U.S. Open (which is already ass-y in so many ways), I fear it'll be nuclear explosion of assiness.